25 August 2015

By Gilberto López y Rivas

Mexican politician and anthropologist. He denounced the Party of Democratic Revolution in 2003 due lack of ethics. He participated in the student movement of 1968. Worked as a deputy in the 54th and 57th Legislatures of Congress of the Union of Mexico.

This article was originally published at teleSUR:

http://www.telesurtv.net/bloggers/Paramilitarismo-y-contrainsurgencia-en-Mexico-una-historia-necesaria---20150825-0002.html.

Paramilitary groups have already existed for more than forty years in our country. During those four decades, paramilitaries have been dedicated to the annihilation of guerrilla organisations, and the violent harassment of student and popular movements.

Paramilitarism is recognised in the military lexicon of all the armies of the world, including the Mexican one. Retired brigadier general, Leopoldo Martínez Caraza, in his book Léxico histórico militar[1], published by the Ministry of National Defense (SEDENA), notes: “Paramilitary: that has an organisation with similar procedures to soldiers, without having this character”. The definition helps, but it is vague and completely insufficient. It doesn't clarify how it comes to have this similarity with the armed forces in organisation, or military procedures.

John Quick is more precise. He defines paramilitaries as: “those groups that are different from the regular armed forces of whatever country or state

1, but that observe the same organisation, equipment, training or mission as the former.”[2] This is a better approximation: militaries as much as paramilitaries have the same organisation, training and mission. However, the origin of the paramilitary organisation is still vague. How does it achieve that organisation? Why does the professional military and the paramilitary have the same mission? Who gives to the latter the same mission?

In that case, the paramilitary groups act by a delegation of power from the state and they collaborate with its ends, but without forming part of the “public administration” strictly speaking. In this way, the paramilitary doesn't define itself only by similarity in its missions or organisation, but because it originates in a delegation of punitive force from the state.

In Mexico, this delegation of functions has come directly from the army, from the intelligence-security bodies, or from the combination of both, but usually under the orders of the Executive Power, in its quality of supreme chief of the armed forces, and always as a direct delegation of the state.

“The Falcons”, one of the first paramilitary groups, was created by the initiative of officials from the army, although under the administration of the then Department of the Federal District. Its members were youths from gangs with military training and leadership, dedicated to the control, infiltration and destruction of the student movement, as well as any guerrilla foco

2 that could have come out of the ranks of it. It is fully documented that this group was created by a colonel of the Mexican army whose services were rewarded afterwards with impunity and military promotion.

Gustavo Castillo García gave detailed information in the newspaper, La Jornada, in 2008, about the most well-know paramilitary group during the so-called “dirty war”, from his documentary research in the General Archive of the Nation:

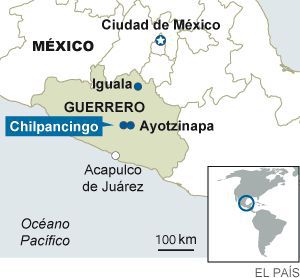

The Special Brigade, as it officially called the White Brigade, integrated in June 1976 a group with 240 elements, among them the police of the capital and the state of Mexico; military and personel from the Federal Directorate of Security (DFS), as well as the Federal Judicial Police, to “investigate and locate by all means the members of the so-called September 23rd Communist League. The order was to limit the activities of the league and detain “the guerrillas that were taking action in the valley of Mexico, according to the documents obtained from the Attorney-General of the Republic's Office (PGR) that are the support of the investigations that are still being carried out around the events that happened during the so-called dirty war. According to the official reports, although the White Brigade formed in 1972 and operated in Guerrero, Sinaloa, Chihuahua, Nuevo León, Jalisco, Puebla and Morelos, it wasn't until June 1976 when the government of Luis Echeverría decided to form a special group that would take action in the City of Mexico, and in which the commands were in the hands of Colonel Francisco Quiroz Hermosillo, Captain Luis de la Barreda Moreno and Miguel Nazar Haro. The consulted documents have their original under protection in the General Archive of the Nation. In them it details “ Plan of Operations Number One: Tracking. The group had 55 vehicles, 253 arms: of them 153 were Browning nine millimetres.[3]

In this way, the state link gives a fundamental element to an understanding attached to the Mexican experience. Based on this experience, I propose the following definition: paramilitary groups are those that have military organisation, equipment and training, to which the state delegates the execution of missions that the regular armed forces can't carry out openly, without that involving the recognition of their existence as part of the monopoly of state violence. Paramilitary groups are illegal and act with impunity because this fits the interests of the state. Paramilitaries consist, then, in the illegal and unpunished exercise of state violence and in the concealment of the origin of that violence.

Historically, paramilitarism has been a phase of counterinsurgency, that one applies when the power of the armed forces isn't sufficient to annihilate insurgent groups, or when the loss of military prestige obliges the creation of a paramilitary arm, linked clandestinely to the military institution.

Mexican military doctrine doesn't call them paramilitaries, but “civilian personnel” and establishes their urgent necessity to control the population during counter-guerrilla operations. The Manual of Irregular Warfare of SEDENA holds that:

531. counter-guerrilla operations form part of the security measures that a commander of a theatre of operations adopts in their rearguard zone, to avoid that regular operations suffer interferences caused by the action of bands of traitors or enemies, to it which the commander of a theatre of operations should employ all organised elements and even the civil population in order to locate, harass and destroy opposing forces[4].

The aim of the utilisation of the civilian population is evident in this paragraph. But here, the necessity of civilian population is random and it is only used in the case of interference by the enemy. However, further on, the Mexican military manual establishes a more permanent and organic manner of utilisation of civilians in rural counter-guerrilla operations:

547. When Mao affirms that “the people are to the guerrillas like water to fish”, undoubtedly that is a saying of lasting validity, as we have already seen that the guerrillas grow and strengthen themselves with the support of the civilian population, but, returning to the example of Mao, for the fish one can make life in the water impossible , agitating it, or introducing elements that are prejudicial to its survival or more ferocious fish that attack it, pursue it and oblige it to disappear or to run the risk of being eaten but these voracious and aggressive fish are nothing more than the counter-guerrillas.[5]

The experience of the Mexican army in the annihilation of the guerrillas that the schoolteacher Lucio Cabañas directed between 1968 and 1974 demonstrated that the use of peasants and gunmen as informants was fundamental to locating, encircling and annihilating the Settlement Brigades of the Party of the Poor.

But the use of civilians goes further: according to the Manual of Irregular Warfare, counter-guerrilla operations are led with civilian or militarised personnel (civilians or police directed by military chiefs). We might look at the following paragraph of the Manual:

551. From it presented earlier, one can establish that counter-guerrilla operations are those that one leads with units of military, civilian or militarised personnel in their own terrain in order to locate, harass and destroy forces made up by enemies and traitors to the homeland that carry out military operations with guerrilla tactics.[6]

The type of counter-guerrilla operations one carries out with civilian personnel and is allocated to the control of the population is pointed out in the Manual:

552. Counter-guerrilla operations comprise of two different forms of interrelated operations that are:

A: Operations to control the civilian population.

B: Tactical counter-guerrilla operations.

553. As one can appreciate, the first form isn't a classical military operation, as it can be led by civilian or militarised personnel, although it is directed, advised and co-ordinated by the military commander of the area, while the tactical counter-guerrilla operations are led by military and militarised units.[7]

According to the Manual of Irregular Warfare, the responsibility of the use of the civilian population falls on the federal government and on the agreements with the governments of the states and diverse authorities in the area of conflict. Paragraph C of point 562 describes in detail:

562. The commanders that plan counter-guerrilla operations and the civilian population are governed by restrictions and agreements that the federal government has with the states and diverse authorities of the places in conflict. In case the problem is provoked in areas occupied by the enemy, the counter-guerrillas will establish co-ordination with the resistance to locate and destroy the groups of traitors.[8]

This paragraph indicates that the responsibility for the use of civilians in counter-guerrilla operations falls directly on the federal government, just as much as on the local and state authorities of the area in conflict. The Manual itself establishes that international law is applicable in the case that the armed forces commit inhumane treatment or criminal acts against the civilian population.

F. Psychological Factors. A population that actively supports the guerrillas increases the possibility of detecting the guerrillas. Generally in our territory we will encounter the support of the population and specifically in liberated areas in which that they opposed the objectives of the enemy force. The population that supports the objectives of the enemy favours their guerrillas. The military objective of destroying the guerrillas acquires greater importance over other considerations, even so the operations must be planned to making sure to minimise the damage to civilian property. The counter-guerrillas should in all cases treat the civilian population in a just and reasonable manner, not rely on our force. Inhumane treatment to criminal acts are serious violations and punishable under international law and our laws[9].

Mexican military doctrine holds that operations of control of the civilian population one exercises through a committee that brings together the military authorities with representatives of the civilian authority and organisations related to the army:

592. To control the civilian population, it is necessary that total co-ordination exists between the military forces and organisations that take part, for which should be established a committee with representatives from all the forces in order that they can plan and co-ordinate their actions under a single command.

593. The forces that normally take part in the operations to control the people and their resources are:

A. Government organisations.

B. Police forces.

C. Military forces.

D. Social, political and economic organisations, like political parties, unions, sports organisations, chambers of commerce, etc.[10]

From 1994, and the same as the paramilitary groups that existed during the internal wars in Guatemala and El Salvador, the paramilitary groups in Chiapas have dedicated themselves to sowing terror in the indigenous communities that sympathise with the EZLN

3, through assassinations, ambushes, burning towns, death threats, expulsions, cattle theft, detention and torture of the support bases or Zapatista militants.

The denunciations of the indigenous people presented since 1995 to the human rights groups that have worked in Chiapas insist that the paramilitary groups operate in co-ordination with the public security corporations, they receive support and training from the Mexican army and that, on occasions, soldiers and police officers that control the towns of the North and the Heights of Chiapas are among the contingents.

In my capacity as a Federal Deputy and president on duty of the Commission of Harmony and Pacification (COCOPA), I presented a complaint in the Attorney-General of the Republic's Office about the existence of paramilitary groups in the state in 1998; in a conversation with the members of this commission of the Congress of the Union with then Attorney-General, Jorge Madrazo Cuellar, this functionary informed us of the existence of at least 12 groups of “presumably armed civilians”, a euphemism to refer to the paramilitaries. A special attorney's office was created for the case, which disappear without shame or glory, years after.

It is evident, however, that the Mexican federal government can't manage, like in the Colombian case, that the paramilitaries remain at the vanguard of the state war against the insurgent groups. In Colombia, as I observed in the department of Putumayo, the paramilitaries were maintaining effective control of extensive zones of the territory of that nation and constituted the semi-clandestine vanguard of the counterinsurgency. Apparently it was already out of the control of the Colombian state, the paramilitaries received funding from landowners and drug traffickers and they had been a force that even had demanded recognition as a belligerent party

4. By recommendation of the CIA advisers, the Colombian army integrated the paramilitary groups into the structure of the national military intelligence.

For all the observers and citizens that have observed the conflict in Chiapas since 1994, the federal and state governments and the Mexican military trusted that the paramilitary forces from the north of Chiapas, “Peace and Justice” and “the Chinchulines”, at the start, might achieve territorial control and make it unnecessary for the army to intervene and sustain direct combat with the Zapatista support bases. However, the mobilisations of the Mexican army that maintained themselves during all these years, indicate that the federal government considered it necessary to maintain its military intensity in the zones of high Zapatista political presence. It is evident, then, that the paramilitaries aren't sufficient for this purpose; even so, the co-existence of military squads and paramilitaries in the same theatres of operation implies the possibility that in Mexico it might occur something which is already routine in other countries: joint operations of paramilitaries and the army.

The government has maintained the use of paramilitaries despite some symptoms of fatigue. The non-government organisations from Chiapas reported ten years ago that the paramilitaries bases existed, in some cases, the same famines that the Zapatistas and those that were discontented because of their leaders, like Samuel Sánchez, head of Peace and Justice, was developing his own hotel and tourism empire in the municipality of Tila, while the indigenous Choles continued in the same poverty. In Tila, even, an Association of ex-Militants of Peace and Justice was created and some paramilitaries without land have carried out occupations of land in the North of Chiapas.

In these years the acronyms and names of groups supposedly disposed to fight against the EZLN and their communities of support have proliferated: “Los Tomates” in Bochil, “Los Chentes” in Tuxtia Gutiérrez, “Los Quintos” in the municipality of Venustiano Carranza, “Los Aguilares" in Bachajón, "los Puñales " in Atenango del Valle, Tepisca and Comitán.

The activities of the Army, far from making clear before the population a real policy of peace of the PRI-PAN

5 federal executives, demonstrates the opposite. The concern provoked in the population by the presence of paramilitaries, the harassment of Zapatista support bases that operate in the Autonomous Municipalities and the Assemblies of Good Government, the major presence of the Army in Chiapas, and in other indigenous regions of the national geography, highlight tactics tending to provoke aggressions and massive displacements in regards to the creation of optimal conditions for the development of big capital in the process of comprehensive occupation on behalf of all types of corporations.

The Federal Army keeps up an intense labour in the Zapatista regions and extensive zones of Guerrero, Oaxaca, Veracruz,among other states with a indigenous population. From the orchestration of intelligence work that has to do with a more precise outline of maps that reflect the dynamic of the population, to understand and control the daily activities of indigenous communities by the full knowledge of their rural roads, their work and the precise location of their habitats, but above all, the scope of natural and strategic resources coveted by transnational companies.

It worth highlighting that phenomena like militarism and its concomitant paramilitarism are given in terms of a new international division of labour that tries to allocate to Mexico and Central American region a role of provider of biodiversity, of a cheap workforce and a exit route for U.S. goods to the markets of the Pacific, besides what the country represents for that other transnational corporation, which is organised crime. With that strategy in mind, Mexican government programs have been put into practice like Attention to the 250 micro-regions, Sustainable Development of the Rainforest and Integral for the Sustainable Development of the Rainforest, etc.

The attempts to dislodge 110 communities in the Lacandona Rainforest and the Integral Reserve of the Montes Azules Biosphere, for example, go precisely in the direction of creating conditions of inhabitability for these communities. Those who have been doing the dirty work, they receive the pressures from transnational companies like the mining companies or like the supposedly ecological corporations, Conservation International. Pulsar Group, Mc Donalds, Disney, Exxon, Ford and Intel, this last one with an investment of 250 million dollars.

To achieve their aims they have had the inestimable support of departments from the federal sphere like Federal Attorney-General's Office of Environmental Protection and the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat). Accompanying these authorities have been the Mexican Army, with their programs of active or latent counterinsurgency and the use of ferocious fish or paramilitaries.

Far from demonstrating a vocation of dialogue and peace, the Army carries out constant patrols in remote indigenous communities. Showing a supreme ignorance of the Constitution, or consciously ignoring the Supreme Law, the Army has awarded itself the functions of a police force, and for this, it assists judicial police, paramilitaries, vendors or religious preachers, in the oldest style of the Linguistic Institute of Summer.

As well as this, the State continues damaging the social fabric through the financing of productive projects that break the traditional vocation of the land and the common forms of collective property and production of the land. Such is the case of it carried out by the past PAN governments that introduced highly predatory and profitable activities, like raising cattle or royal palm. In this sense, some years ago, they carried out activities on behalf of the coffee growers from Ocosingo (ORCAO), who, with the help of official programs, developed economic activities without the consent of the community, increasing the violent actions against it and the autonomous authorities.

Summarising, paramilitarism serves the ends of counterinsurgency, destroying or damaging severely the social fabric that supports the guerrillas. It acts under the most diverse expressions. Attacking providers of social services in the camps of displaced peoples, causing conditions of inhabitability in indigenous and peasant communities that provoke displacements, making common cause with civil authorities, exercising harassment through the action of bribable judges, infiltrating religious associations, carrying out intelligence work, suggesting developmentalist dilemmas that cause environmental damage, assigning as enemies of development the communities that refuse to follow the logic of capitalist profit, with its consequent instability, and above all causing or increasing the spiral of violence in the communities making from this a way of life through drug trafficking, militarisation and criminalisation of opposition.

The features of many communities has changed due to militarism, organised crime and paramilitarism. The arrival of phenomena like prostitution, drug addiction and drug trafficking aren't natural circumstances, but the result of a strategy of penetration of capital, with its multiple armed wings at the service of the State.

The autonomous praxis expressed precisely in the Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities and Assemblies of Good Government, in the communities that adhere to the CRAC

6, of Guerrero, in Cherán, Michoacán, or in municipalities of Oaxaca, by mentioning, the most visible cases, has called attention and has meant the increase of the military activities, and the whole gamut of armed groups related to organised crime and the paramilitaries. These experiences, by acquiring importance through their de facto autonomies have put themselves once more in the sights of the State. By displaying strategies of resistance, protected in international jurisprudence, like those expressed in Convention 169 of the OIT

7 and Universal Declaration of Rights of Indigenous Peoples issued by the United Nations, the autonomous communities give an example of anti-capitalist struggle.

Therefore, any future project to rescue the nation requires debating in depth the constitutional tasks of the armed forces with the aim of totally shifting it from its present condition: which in fact is a truly a force of occupation of the peoples. A project to democratise the country requires strengthening civil and legislative control of the armed forces and definitive disappearance of of the fourth illegal, secret, armed force that is grouped under the paramilitaries and on which the government bases its undercover operations against the EZLN, other armed groups and the whole gamut of civilian organisations that take part in peaceful resistance in the national territory.

[1]Leopoldo Martínez Caraza, Léxico histórico militar. Biblioteca del oficial mexicano. Secretaria de la Defensa Nacional, México, 1993.

[2] John Quick. Dictionary of weapons and military terms. McGraw Hill. Estados Unidos, 1973.

[3]“El gobierno creó en 1976 brigada especial para “aplastar” a guerrilleros en el valle de México” La Jornada, 7 de julio de 2008.

[4] Manual de guerra irregular. Operaciones de contraguerrilla o restauración del orden. T. II, SEDENA, enero de 1995.

[5] Ibíd.

[6] Ibíd.

[7] Ibíd.

[8] Ibíd.

[9] Ibíd.

[10] Ibíd.

Translator's notes: